William Dalrymple The Guardian, Saturday 12 November 2005 Article history

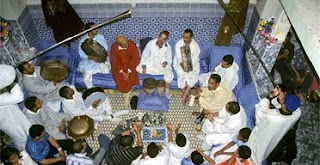

Everyone back to mine... a Sufi house purification ceremony. Photographer: Simon Broughton.

In 1195, a travelling scholar and mystic from Spain arrived at Fes, the oldest of the imperial capitals of Morocco. Ibn Arabi was one of the great minds of his day, a standard bearer of Islamic Spain at the height of its scientific and philosophical achievement, and the tolerant and pluralistic university town of Fes was the perfect setting for his talents. In the 12th century, it was one of the great centres of learning of the Arab world, packed with libraries and schools, and with a university founded over 200 years before Oxford and Cambridge.

In 1195, a travelling scholar and mystic from Spain arrived at Fes, the oldest of the imperial capitals of Morocco. Ibn Arabi was one of the great minds of his day, a standard bearer of Islamic Spain at the height of its scientific and philosophical achievement, and the tolerant and pluralistic university town of Fes was the perfect setting for his talents. In the 12th century, it was one of the great centres of learning of the Arab world, packed with libraries and schools, and with a university founded over 200 years before Oxford and Cambridge.

While staying in Fes, Ibn Arabi experienced a moment of blinding spiritual illumination, reaching what he called "the Abode of Light". In the aftermath, he sat in his cell attempting to reconcile ancient Greek philosophy with the visionary currents of mystical Islam, and he began work on what would eventually be his great masterpiece - still a central text of Islamic mysticism - the Meccan Revelations.

Today, almost all the mosques, madrasas, bazaars and caravanserais than Ibn Arabi knew 800 years ago are still extant, and mostly unchanged. Lying between the olive groves of the Rif mountains and the cedar-wooded summits of the Middle Atlas, Fes is one of the most perfectly preserved medieval cities in the world, a dense warren of streets girdled round with castellated mud-brick walls which look out over pale hills dotted with whitewashed farmsteads and terraces of silver-leafed olive trees.

The city's roofs are still clad with lime-green tiles, the view over them broken every so often with the vertical punctuation of thin, pencil-like minarets and narrow plumes of black smoke from the Fes potteries. Then, as now, the streets are so narrow that you have to press yourself against the shops to avoid being crushed by donkeys laden with wood, carpets or spices. But it is not just the groaning medieval fabric of the city that has survived. The old loom of the city's life is also still intact, with its medieval guilds and communal bakeries, its hammams and water-pipes and mint tea shops, its textile traders and mule-driving porters. Most of all, Fes is still a major centre for the Sufi brotherhoods who were so much a part of the life of Ibn Arabi during his stay in the town.

In its setting, Fes is not unlike Jerusalem, with its steep, narrow bazaars and dense concentration of holy shrines; but while Jerusalem is ever a tinder box of religious conflict and ethnic strife, Fes is a town obviously at ease with itself, and the gentle spirit of its Sufi Islam is quite different from the rival fanaticisms that possess the Middle East. The landscape, too, is greener and less arid than Jerusalem, feeling closer to the wide rolling plains of Andalucia than the white rock and goat scrub of the Levant.

Madrasas have a somewhat sinister reputation today, but it was these institutions that kick-started the revival of medieval European learning. As late as the 14th century, European scholars would travel to the Islamic world to pick up the advanced learning then on offer in the madrasas of Spain and Morocco. The open-mindedness of the immigrant Christian scholars was returned by the intellectuals of Fes resident in the city's madrasas. Ibn Arabi for one was clear that love was more important than religious affiliation.

Ibn Arabi's flame is still being carried in modern Fes, most notably by the Sufi musical impresario Faouzi Skali, who over the last decade has seen his summer Fes festival turn into one of the world's leading venues for sacred music. The festival is a distinctly Sufi response to political developments. It was prompted by the first Gulf War and the ensuing polarisation of the Arab world and the west. "Muslims had a stereotypical view of the west and vice versa," Faouzi told me. "I wanted to create a place where people could meet and discover the beauty of each religion and culture. In Fes, people can see another image of Islam - a message which it can pass on to the world today."

The idea of the Fes Festival of World Sacred Music is a simple one: to juxtapose religious music from all over the world - from any creed or faith. This year, audiences were regaled by the sacred ragas of Hindustani music performed by Ravi and Anushka Shankar. The highlight last year was the astonishing Senegalese singer Youssou N'Dour and his Sufi-inspired album, Egypt.

Faouzi sees Sufism at the heart of this work. "I believe that within Islam, Sufism has a major role to play today," he says. "The world is not uniform. There's a wealth of spiritual traditions that it's important to know and preserve. That's what we, and the next generation, need now or we will have a world without soul." Ibn Arabi would have agreed.

Every day at the Fes festival, there are performances staged beneath the shade of a giant holm oak in the courtyard garden of a 19th-century palace, followed in the late evening by a grand concert at an open-air theatre. This is in a fabulous illuminated courtyard created by closing off one of the 13th-century gateways to the royal palace.

But it is not here so much as in the backstreets that some of the most exciting music is on offer, and it comes from the different Sufi groups which form the real heartbeat of Morocco. In particular, around midnight in the old garden of Tazi Pasha, the local Sufi brotherhoods play to a mixed crowd of street urchins, writers, artists and fellow musicians, all sprawled over cushions beside an old fountain.

At one such impromptu concert I met 'Abd Nebi Zizi. He was one of the city's leather workers who labour away in the foul-smelling tanneries that were founded in the 14th century and are still exporting leather today.

He was also, I soon learned, a member of the Aissawas, one of the most widespread Sufi brotherhoods in Morocco. The Aissawas, I knew, were celebrated for their spectacular music, and by good fortune Zizi was about to hold a major Sufi musical ceremony at his house: "Every year around the Prophet's Birthday," said Zizi, "we Aissawas do an alms ceremony. We wish goodbye to the past year with its good and bad events, and try to bring good luck on our house for the year ahead."

Zizi was throwing a house-purification ceremony, in order to propitiate his family's resident djinns. Muslims, he explained, believe that when the world was new and God made mankind from clay, he made another race like us in all things, but fashioned from fire. The djinns, said Zizi, are invisible to the naked eye. They appear in the Koran and are respected all over the Islamic world, but it is in Morocco that djinns have received most elaboration.

The following night I arranged to meet Zizi at the tanneries and he led me through the dark and narrow winding streets to his family riad. There Zizi's entire extended family were in the process of gathering and preparing the feast. Shortly after 10pm, the sound of trumpets could be heard outside the house and everyone poured out to greet the musicians.

In the dark, 11 musicians were heading down the street, some with trumpets, others with drums and oboes, and, as they walked, the entire neighbourhood appeared to escort them, the men walking four abreast in their long jellabas with arms linked, while others carried torches and burning splints. Women in headscarves peered down from balconies while children ran along in front of the musicians laughing and playing. By the time the musicians neared the house, there must have been a procession of at least 150 people.

The musicians settled in the central covered courtyard where they ranged themselves around the divans, playing all the time so that the insistent hand drums echoed off the walls and ceilings, the volume rising to fill the enclosed space. Once everyone had gathered, the ceremony proper began with the rhythmic chanting of the 99 names of God. Koranic verses were recited, the phrases passing from group to group. Then the music began with family members taking turns to accompany the musicians with tablas and cymbals. As the evening progressed, the tone grew increasingly loud and exuberant. The music was driven by powerful rhythmic grooves, like a sort of spiritual jazz, the oboes on top improvising repeated musical phrases pushing up the intensity.

As the volume grew, some of the women began to sway with a lost look on their faces, falling into the trance-like state that Moroccans believe to signal the presence and possession of the djinns. It certainly looked a little alarming, but was clearly a way of easing pent-up anxieties in a way that's acceptable in a deeply conservative society. It was a sort of safety valve - something like a rave, but with better, less monotonous music. By the time I left, towards five in the morning, with dawn breaking over the Atlas, I had no doubt that it was one of the most exciting musical evenings I have ever participated in.

"This is the way we get relief from our work," explained Zizi as he wished me goodbye. "This is the way we end our family and spiritual problems. If people are sick it gives them help physically, mentally and psychologically."

He put a hand on my shoulder: "When they listen to this music, the djinns are satisfied and bless our house, but it's not just the djinns. It is us, too. For us, this ceremony brings us together and relieves us. After this, we feel at one with the world."

· William Dalrymple's most recent book, White Mughals, won the Wolfson Prize for history. He is now at work on a Mughal Quartet, four books telling the story of the Great Mughals from the time of Babur to the last Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. The first volume will be published by Bloomsbury next autumn.

星期三,2010年8月25日讓我們恍惚威廉達爾林普爾衛報,2005年11月12號星期六的歷史條

大家回到我的...一蘇菲房子淨化儀式。攝影師:西蒙勞頓。1195,旅行學者和來自西班牙 的神秘抵達 Fes的,最古老的帝國首都的摩洛哥。伊本阿拉比是一個偉大的思想家,他一 天,一個伊斯蘭西班牙的旗手在高度的科學和哲學成果,寬容和多元化的大學城,是完美的FeS設定自己的才華。在12世紀,這是一項偉大的學習中心的阿拉伯世界,擠滿了圖書館和學校,並與大學成立200多年以前牛津大學和劍橋大學。

而留在Fes,伊本阿拉比經歷了片刻的致盲精神光照,達到了他所謂的“精舍之光”。在此之後,他坐在他的牢房試圖調和古希臘哲學與伊斯蘭教的神秘有遠見的電流,而他開始工作是什麼,最終他的偉大傑作 - 這仍然是中央文本伊斯蘭神秘主義 - 對麥加的啟示。

今 天,幾乎所有的清真寺,宗教學校,集貿市場和伊本阿拉比知道caravanserais比800年前還是現存的,而且大多不變。躺在橄欖樹之間的里夫山脈和雪松,林地首腦會議在中東阿特拉斯,非斯是一個最完美的保存完好的中世紀城市的世界, 一個密集的街道低低的地平線沃倫圓蜂窩泥磚牆這一下了在蒼白的山丘點綴著粉刷農莊和露台銀葉橄欖樹。

城市的屋頂是用石灰仍然穿著綠色的瓷磚,認為對他們打破所有經常與垂直標點符號薄,鉛筆般的尖塔,縮小柱黑煙從 Fes的陶器。當時和現在一樣,街道是如此狹窄,你必須按自己對店鋪,以免被壓死驢拉丹與木材,地毯或香 料。但它不僅是面料的呻吟中世紀的城市,已經活了下來。舊織機城市的生活也仍然完好無損,其中世紀的行會和社區麵包店,它的浴池和水管道和薄荷茶商店,其紡織商和騾子駕駛搬運工。最重要的是,非斯仍然是一個主要中心的蘇菲的兄弟誰是與其說是生活的一部分,在他的伊本阿拉比留在城裡。

在其設置,非斯是不是不像耶路撒冷,其陡峭,狹窄的集貿市場和密集的濃度聖地,但同時耶路撒冷是永遠的火種盒的宗 教衝突和種族紛爭,非斯,顯然是一個鎮在緩和與本身,溫柔的精神是伊斯蘭教的蘇菲完全不同的對手 fanaticisms是擁有中東地區。景觀,也更綠,少乾旱比耶路撒冷,感覺更接近安 達盧西亞廣泛的平原比白山羊磨砂岩和地中海東部。

宗教學校有一個有點陰險 的聲譽今天,但正是這些機構的球啟動了中世紀歐洲的復興學習。遲至14世紀,歐洲學者將 前往伊斯蘭世界拿起提供先進的學習然後在西班牙和摩洛哥的宗教學校。開放的胸襟的移民基督教學者知識分子退 回了FeS的居住在城市的宗教學校。伊本阿拉比一,顯然比愛更重要的宗教信仰。

伊本阿拉比的火焰仍在進行現代 Fes的,最顯著的蘇菲音樂掌門 Faouzi Skali,誰在過去十年,他的夏季Fes的節日變成一個世界領先的場地,讓神聖的音樂。藝 術節是一個明顯的蘇菲回應政治的發展。這是提示的第一次海灣戰爭以及由此產生兩極分化阿拉伯世界和西方。 “穆斯林有成見的西方,反之亦然,”Faouzi告訴我。 “我想 創造一個地方,人們可以發現美的滿足和各宗教和文化。在Fes,人們可以看到另一幅圖像的伊斯蘭教 - 一個消息,它可以傳遞到今天的世界。”

這個想法在非斯聖樂節世界是一個簡單的:宗教音樂並列世界各地 - 從任何信仰或信仰。今年,觀眾們 regaled的神聖拉格音樂演出由印度斯坦拉維尚卡爾和Anushka。去年活動的高潮是驚人的塞內加爾歌手Youssou N'Dour及其他蘇菲啟發專輯,埃及。

Faouzi看到蘇菲的心在此工作。 “我相信在伊斯蘭教蘇菲主義有著重大作用的今 天,”他說。 “世界是不統一。有一個豐富的精神傳統,它的重要認識和保護。這就是我們和下一代,現在需要 的,否則我們將有一個世界沒有靈魂。”伊本阿拉比會同意。

每天在Fes的節日,有表演樹蔭下舉行一個巨大的聖櫟在庭院花園一座19世紀的宮殿,隨後在晚上的盛大音樂會在一 個露天劇場。這是一個神話般的照明庭院創建封山育林一個 13世紀的皇家宮殿網關。

但它是不是在這裡這麼多的後街小巷中,一些最令人興奮的音樂發行,它來自於不同的蘇菲群體構成了真正的心跳摩洛哥。尤其是午夜時分在老花園塔子帕夏,當地蘇菲兄弟會發揮一個混合人群的街頭頑童,作家,藝術家和音樂家的同胞,都趴 在墊子旁邊的一個老噴泉。

在一個這樣的即興演唱我遇見了,阿布杜拉 Nebi滋滋。他是一個城市的皮革工人誰的勞動遠在惡臭的制革廠的是成立於 14世紀,今天仍然是出口皮革。

他也是,我很快了解到,一成員 Aissawas,其中一個最普遍的蘇菲在摩洛哥的兄弟。該 Aissawas,我知道,慶祝了他們的精彩音樂,和好運氣滋滋即將舉行的重大蘇菲音樂典禮在他的家裡說:“每年約先知的生日,說:”滋滋“我們 Aissawas做一個施捨儀式。我們希望告別了過去的一年,它的好的和壞的事件,並嘗試對我們帶來好運, 來年的房子。“

滋滋的房子扔淨化儀式,以撫慰他的家庭的居住 djinns。穆斯林,他解釋說,認為,當世界是新的,神造人原是由粘土,他在另一場比賽都像我們這樣的事 情,但老式火。該 djinns說,滋滋,是肉眼看不到的。它們出現在古蘭經和得到尊重伊斯蘭世界各地,但它是在摩洛哥djinns已收到最闡述。

第二天晚上我安排,以應付在滋滋的制革廠和他帶領我走出黑暗,狹窄蜿蜒的街道,他的家人里亞德。有滋滋的整個大家庭在這個過程中收集和準備的盛宴。不久後,下午10 時,聲音的喇叭可以聽見外面的房子,每個人都倒出來迎接的音樂家。

在黑暗中,11個音樂家的標題在街上,一些小號,雙簧管及其他與鼓,而且,因為他們走了,整個社區出現護送他們,男子四人一排走在漫長 的jellabas與武器聯繫在一起,而燃燒的火把和他人進行夾板。戴頭巾的婦女從陽台上向下張望,而孩子們一起跑在前面的音樂家笑,玩耍。由當時的音樂家接近房子,一定有一個遊行,至少150人。

樂師們在中央結算所涵蓋的庭院,他們不等自己周圍的長沙發,玩的時間,使所有倔強的手鼓聲迴盪關閉牆壁和天花板,體 積增加,以填補封閉的空間。一旦每個人都已經聚集,儀式才真正開始誦經的節奏的99名神。古蘭經經文的背誦,路過的短語從組到組。然後,音樂開始與家人輪流陪音樂家與塔布拉斯 和鈸。由於晚上的進展,語氣變得越來越響亮和旺盛。音樂節奏是受到強大的凹槽,有點像一個精神爵士,即興重複上面雙簧管音樂短語推動的力度。

隨著量的增加,一些女性開始搖晃會失去看他們的臉,落入恍惚狀態,相信摩洛哥人信號的存在和佔有的djinns。這當然看起來有點令人震驚,但顯然是一種方式,緩解壓抑的憂慮在某種程度上這是可以接受的一個極為保守的社會。這是一個有點安全閥 - 這就像一個狂野,但更出色,更單調的音樂。我離開的時候,對五早上,打破了黎明的圖集,我毫不懷疑,這是一個最令人興奮的音樂晚會我也參加過英寸

“這就是我們從我們的工作得到救濟,解釋說:”滋滋的,他希望我說再見。 “這是我們的方式結束我們的家庭和精神生活的問題。如果人們生病也讓他們幫助身體,精神和心理上。”

他把一隻手放在我的肩膀:“當他們聽這個音樂,djinns感到滿意,並祝福我們的房子,但它不只是 djinns。這是我們也是。對於我們來說,這個儀式使我們走到一起並減輕我們。在此之 後,我們覺得在一個與世界。“

·威廉達爾林普爾的最新 著作,白蒙兀兒,贏得了歐勝獎的歷史。他現在工作在莫臥兒四方,四書講故事的大莫臥兒從 時間到末代皇帝巴布爾,哈杜爾沙阿 Zafar。第一冊將於明年秋季由 Bloomsbury出版。

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2010

Everyone back to mine... a Sufi house purification ceremony. Photographer: Simon Broughton.

In 1195, a travelling scholar and mystic from Spain arrived at Fes, the oldest of the imperial capitals of Morocco. Ibn Arabi was one of the great minds of his day, a standard bearer of Islamic Spain at the height of its scientific and philosophical achievement, and the tolerant and pluralistic university town of Fes was the perfect setting for his talents. In the 12th century, it was one of the great centres of learning of the Arab world, packed with libraries and schools, and with a university founded over 200 years before Oxford and Cambridge.

In 1195, a travelling scholar and mystic from Spain arrived at Fes, the oldest of the imperial capitals of Morocco. Ibn Arabi was one of the great minds of his day, a standard bearer of Islamic Spain at the height of its scientific and philosophical achievement, and the tolerant and pluralistic university town of Fes was the perfect setting for his talents. In the 12th century, it was one of the great centres of learning of the Arab world, packed with libraries and schools, and with a university founded over 200 years before Oxford and Cambridge.While staying in Fes, Ibn Arabi experienced a moment of blinding spiritual illumination, reaching what he called "the Abode of Light". In the aftermath, he sat in his cell attempting to reconcile ancient Greek philosophy with the visionary currents of mystical Islam, and he began work on what would eventually be his great masterpiece - still a central text of Islamic mysticism - the Meccan Revelations.

Today, almost all the mosques, madrasas, bazaars and caravanserais than Ibn Arabi knew 800 years ago are still extant, and mostly unchanged. Lying between the olive groves of the Rif mountains and the cedar-wooded summits of the Middle Atlas, Fes is one of the most perfectly preserved medieval cities in the world, a dense warren of streets girdled round with castellated mud-brick walls which look out over pale hills dotted with whitewashed farmsteads and terraces of silver-leafed olive trees.

The city's roofs are still clad with lime-green tiles, the view over them broken every so often with the vertical punctuation of thin, pencil-like minarets and narrow plumes of black smoke from the Fes potteries. Then, as now, the streets are so narrow that you have to press yourself against the shops to avoid being crushed by donkeys laden with wood, carpets or spices. But it is not just the groaning medieval fabric of the city that has survived. The old loom of the city's life is also still intact, with its medieval guilds and communal bakeries, its hammams and water-pipes and mint tea shops, its textile traders and mule-driving porters. Most of all, Fes is still a major centre for the Sufi brotherhoods who were so much a part of the life of Ibn Arabi during his stay in the town.

In its setting, Fes is not unlike Jerusalem, with its steep, narrow bazaars and dense concentration of holy shrines; but while Jerusalem is ever a tinder box of religious conflict and ethnic strife, Fes is a town obviously at ease with itself, and the gentle spirit of its Sufi Islam is quite different from the rival fanaticisms that possess the Middle East. The landscape, too, is greener and less arid than Jerusalem, feeling closer to the wide rolling plains of Andalucia than the white rock and goat scrub of the Levant.

Madrasas have a somewhat sinister reputation today, but it was these institutions that kick-started the revival of medieval European learning. As late as the 14th century, European scholars would travel to the Islamic world to pick up the advanced learning then on offer in the madrasas of Spain and Morocco. The open-mindedness of the immigrant Christian scholars was returned by the intellectuals of Fes resident in the city's madrasas. Ibn Arabi for one was clear that love was more important than religious affiliation.

Ibn Arabi's flame is still being carried in modern Fes, most notably by the Sufi musical impresario Faouzi Skali, who over the last decade has seen his summer Fes festival turn into one of the world's leading venues for sacred music. The festival is a distinctly Sufi response to political developments. It was prompted by the first Gulf War and the ensuing polarisation of the Arab world and the west. "Muslims had a stereotypical view of the west and vice versa," Faouzi told me. "I wanted to create a place where people could meet and discover the beauty of each religion and culture. In Fes, people can see another image of Islam - a message which it can pass on to the world today."

The idea of the Fes Festival of World Sacred Music is a simple one: to juxtapose religious music from all over the world - from any creed or faith. This year, audiences were regaled by the sacred ragas of Hindustani music performed by Ravi and Anushka Shankar. The highlight last year was the astonishing Senegalese singer Youssou N'Dour and his Sufi-inspired album, Egypt.

Faouzi sees Sufism at the heart of this work. "I believe that within Islam, Sufism has a major role to play today," he says. "The world is not uniform. There's a wealth of spiritual traditions that it's important to know and preserve. That's what we, and the next generation, need now or we will have a world without soul." Ibn Arabi would have agreed.

Every day at the Fes festival, there are performances staged beneath the shade of a giant holm oak in the courtyard garden of a 19th-century palace, followed in the late evening by a grand concert at an open-air theatre. This is in a fabulous illuminated courtyard created by closing off one of the 13th-century gateways to the royal palace.

But it is not here so much as in the backstreets that some of the most exciting music is on offer, and it comes from the different Sufi groups which form the real heartbeat of Morocco. In particular, around midnight in the old garden of Tazi Pasha, the local Sufi brotherhoods play to a mixed crowd of street urchins, writers, artists and fellow musicians, all sprawled over cushions beside an old fountain.

At one such impromptu concert I met 'Abd Nebi Zizi. He was one of the city's leather workers who labour away in the foul-smelling tanneries that were founded in the 14th century and are still exporting leather today.

He was also, I soon learned, a member of the Aissawas, one of the most widespread Sufi brotherhoods in Morocco. The Aissawas, I knew, were celebrated for their spectacular music, and by good fortune Zizi was about to hold a major Sufi musical ceremony at his house: "Every year around the Prophet's Birthday," said Zizi, "we Aissawas do an alms ceremony. We wish goodbye to the past year with its good and bad events, and try to bring good luck on our house for the year ahead."

Zizi was throwing a house-purification ceremony, in order to propitiate his family's resident djinns. Muslims, he explained, believe that when the world was new and God made mankind from clay, he made another race like us in all things, but fashioned from fire. The djinns, said Zizi, are invisible to the naked eye. They appear in the Koran and are respected all over the Islamic world, but it is in Morocco that djinns have received most elaboration.

The following night I arranged to meet Zizi at the tanneries and he led me through the dark and narrow winding streets to his family riad. There Zizi's entire extended family were in the process of gathering and preparing the feast. Shortly after 10pm, the sound of trumpets could be heard outside the house and everyone poured out to greet the musicians.

In the dark, 11 musicians were heading down the street, some with trumpets, others with drums and oboes, and, as they walked, the entire neighbourhood appeared to escort them, the men walking four abreast in their long jellabas with arms linked, while others carried torches and burning splints. Women in headscarves peered down from balconies while children ran along in front of the musicians laughing and playing. By the time the musicians neared the house, there must have been a procession of at least 150 people.

The musicians settled in the central covered courtyard where they ranged themselves around the divans, playing all the time so that the insistent hand drums echoed off the walls and ceilings, the volume rising to fill the enclosed space. Once everyone had gathered, the ceremony proper began with the rhythmic chanting of the 99 names of God. Koranic verses were recited, the phrases passing from group to group. Then the music began with family members taking turns to accompany the musicians with tablas and cymbals. As the evening progressed, the tone grew increasingly loud and exuberant. The music was driven by powerful rhythmic grooves, like a sort of spiritual jazz, the oboes on top improvising repeated musical phrases pushing up the intensity.

As the volume grew, some of the women began to sway with a lost look on their faces, falling into the trance-like state that Moroccans believe to signal the presence and possession of the djinns. It certainly looked a little alarming, but was clearly a way of easing pent-up anxieties in a way that's acceptable in a deeply conservative society. It was a sort of safety valve - something like a rave, but with better, less monotonous music. By the time I left, towards five in the morning, with dawn breaking over the Atlas, I had no doubt that it was one of the most exciting musical evenings I have ever participated in.

"This is the way we get relief from our work," explained Zizi as he wished me goodbye. "This is the way we end our family and spiritual problems. If people are sick it gives them help physically, mentally and psychologically."

He put a hand on my shoulder: "When they listen to this music, the djinns are satisfied and bless our house, but it's not just the djinns. It is us, too. For us, this ceremony brings us together and relieves us. After this, we feel at one with the world."

· William Dalrymple's most recent book, White Mughals, won the Wolfson Prize for history. He is now at work on a Mughal Quartet, four books telling the story of the Great Mughals from the time of Babur to the last Emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar. The first volume will be published by Bloomsbury next autumn.

星期三,2010年8月25日讓我們恍惚威廉達爾林普爾衛報,2005年11月12號星期六的歷史條

大家回到我的...一蘇菲房子淨化儀式。攝影師:西蒙勞頓。1195,旅行學者和來自西班牙 的神秘抵達 Fes的,最古老的帝國首都的摩洛哥。伊本阿拉比是一個偉大的思想家,他一 天,一個伊斯蘭西班牙的旗手在高度的科學和哲學成果,寬容和多元化的大學城,是完美的FeS設定自己的才華。在12世紀,這是一項偉大的學習中心的阿拉伯世界,擠滿了圖書館和學校,並與大學成立200多年以前牛津大學和劍橋大學。

而留在Fes,伊本阿拉比經歷了片刻的致盲精神光照,達到了他所謂的“精舍之光”。在此之後,他坐在他的牢房試圖調和古希臘哲學與伊斯蘭教的神秘有遠見的電流,而他開始工作是什麼,最終他的偉大傑作 - 這仍然是中央文本伊斯蘭神秘主義 - 對麥加的啟示。

今 天,幾乎所有的清真寺,宗教學校,集貿市場和伊本阿拉比知道caravanserais比800年前還是現存的,而且大多不變。躺在橄欖樹之間的里夫山脈和雪松,林地首腦會議在中東阿特拉斯,非斯是一個最完美的保存完好的中世紀城市的世界, 一個密集的街道低低的地平線沃倫圓蜂窩泥磚牆這一下了在蒼白的山丘點綴著粉刷農莊和露台銀葉橄欖樹。

城市的屋頂是用石灰仍然穿著綠色的瓷磚,認為對他們打破所有經常與垂直標點符號薄,鉛筆般的尖塔,縮小柱黑煙從 Fes的陶器。當時和現在一樣,街道是如此狹窄,你必須按自己對店鋪,以免被壓死驢拉丹與木材,地毯或香 料。但它不僅是面料的呻吟中世紀的城市,已經活了下來。舊織機城市的生活也仍然完好無損,其中世紀的行會和社區麵包店,它的浴池和水管道和薄荷茶商店,其紡織商和騾子駕駛搬運工。最重要的是,非斯仍然是一個主要中心的蘇菲的兄弟誰是與其說是生活的一部分,在他的伊本阿拉比留在城裡。

在其設置,非斯是不是不像耶路撒冷,其陡峭,狹窄的集貿市場和密集的濃度聖地,但同時耶路撒冷是永遠的火種盒的宗 教衝突和種族紛爭,非斯,顯然是一個鎮在緩和與本身,溫柔的精神是伊斯蘭教的蘇菲完全不同的對手 fanaticisms是擁有中東地區。景觀,也更綠,少乾旱比耶路撒冷,感覺更接近安 達盧西亞廣泛的平原比白山羊磨砂岩和地中海東部。

宗教學校有一個有點陰險 的聲譽今天,但正是這些機構的球啟動了中世紀歐洲的復興學習。遲至14世紀,歐洲學者將 前往伊斯蘭世界拿起提供先進的學習然後在西班牙和摩洛哥的宗教學校。開放的胸襟的移民基督教學者知識分子退 回了FeS的居住在城市的宗教學校。伊本阿拉比一,顯然比愛更重要的宗教信仰。

伊本阿拉比的火焰仍在進行現代 Fes的,最顯著的蘇菲音樂掌門 Faouzi Skali,誰在過去十年,他的夏季Fes的節日變成一個世界領先的場地,讓神聖的音樂。藝 術節是一個明顯的蘇菲回應政治的發展。這是提示的第一次海灣戰爭以及由此產生兩極分化阿拉伯世界和西方。 “穆斯林有成見的西方,反之亦然,”Faouzi告訴我。 “我想 創造一個地方,人們可以發現美的滿足和各宗教和文化。在Fes,人們可以看到另一幅圖像的伊斯蘭教 - 一個消息,它可以傳遞到今天的世界。”

這個想法在非斯聖樂節世界是一個簡單的:宗教音樂並列世界各地 - 從任何信仰或信仰。今年,觀眾們 regaled的神聖拉格音樂演出由印度斯坦拉維尚卡爾和Anushka。去年活動的高潮是驚人的塞內加爾歌手Youssou N'Dour及其他蘇菲啟發專輯,埃及。

Faouzi看到蘇菲的心在此工作。 “我相信在伊斯蘭教蘇菲主義有著重大作用的今 天,”他說。 “世界是不統一。有一個豐富的精神傳統,它的重要認識和保護。這就是我們和下一代,現在需要 的,否則我們將有一個世界沒有靈魂。”伊本阿拉比會同意。

每天在Fes的節日,有表演樹蔭下舉行一個巨大的聖櫟在庭院花園一座19世紀的宮殿,隨後在晚上的盛大音樂會在一 個露天劇場。這是一個神話般的照明庭院創建封山育林一個 13世紀的皇家宮殿網關。

但它是不是在這裡這麼多的後街小巷中,一些最令人興奮的音樂發行,它來自於不同的蘇菲群體構成了真正的心跳摩洛哥。尤其是午夜時分在老花園塔子帕夏,當地蘇菲兄弟會發揮一個混合人群的街頭頑童,作家,藝術家和音樂家的同胞,都趴 在墊子旁邊的一個老噴泉。

在一個這樣的即興演唱我遇見了,阿布杜拉 Nebi滋滋。他是一個城市的皮革工人誰的勞動遠在惡臭的制革廠的是成立於 14世紀,今天仍然是出口皮革。

他也是,我很快了解到,一成員 Aissawas,其中一個最普遍的蘇菲在摩洛哥的兄弟。該 Aissawas,我知道,慶祝了他們的精彩音樂,和好運氣滋滋即將舉行的重大蘇菲音樂典禮在他的家裡說:“每年約先知的生日,說:”滋滋“我們 Aissawas做一個施捨儀式。我們希望告別了過去的一年,它的好的和壞的事件,並嘗試對我們帶來好運, 來年的房子。“

滋滋的房子扔淨化儀式,以撫慰他的家庭的居住 djinns。穆斯林,他解釋說,認為,當世界是新的,神造人原是由粘土,他在另一場比賽都像我們這樣的事 情,但老式火。該 djinns說,滋滋,是肉眼看不到的。它們出現在古蘭經和得到尊重伊斯蘭世界各地,但它是在摩洛哥djinns已收到最闡述。

第二天晚上我安排,以應付在滋滋的制革廠和他帶領我走出黑暗,狹窄蜿蜒的街道,他的家人里亞德。有滋滋的整個大家庭在這個過程中收集和準備的盛宴。不久後,下午10 時,聲音的喇叭可以聽見外面的房子,每個人都倒出來迎接的音樂家。

在黑暗中,11個音樂家的標題在街上,一些小號,雙簧管及其他與鼓,而且,因為他們走了,整個社區出現護送他們,男子四人一排走在漫長 的jellabas與武器聯繫在一起,而燃燒的火把和他人進行夾板。戴頭巾的婦女從陽台上向下張望,而孩子們一起跑在前面的音樂家笑,玩耍。由當時的音樂家接近房子,一定有一個遊行,至少150人。

樂師們在中央結算所涵蓋的庭院,他們不等自己周圍的長沙發,玩的時間,使所有倔強的手鼓聲迴盪關閉牆壁和天花板,體 積增加,以填補封閉的空間。一旦每個人都已經聚集,儀式才真正開始誦經的節奏的99名神。古蘭經經文的背誦,路過的短語從組到組。然後,音樂開始與家人輪流陪音樂家與塔布拉斯 和鈸。由於晚上的進展,語氣變得越來越響亮和旺盛。音樂節奏是受到強大的凹槽,有點像一個精神爵士,即興重複上面雙簧管音樂短語推動的力度。

隨著量的增加,一些女性開始搖晃會失去看他們的臉,落入恍惚狀態,相信摩洛哥人信號的存在和佔有的djinns。這當然看起來有點令人震驚,但顯然是一種方式,緩解壓抑的憂慮在某種程度上這是可以接受的一個極為保守的社會。這是一個有點安全閥 - 這就像一個狂野,但更出色,更單調的音樂。我離開的時候,對五早上,打破了黎明的圖集,我毫不懷疑,這是一個最令人興奮的音樂晚會我也參加過英寸

“這就是我們從我們的工作得到救濟,解釋說:”滋滋的,他希望我說再見。 “這是我們的方式結束我們的家庭和精神生活的問題。如果人們生病也讓他們幫助身體,精神和心理上。”

他把一隻手放在我的肩膀:“當他們聽這個音樂,djinns感到滿意,並祝福我們的房子,但它不只是 djinns。這是我們也是。對於我們來說,這個儀式使我們走到一起並減輕我們。在此之 後,我們覺得在一個與世界。“

·威廉達爾林普爾的最新 著作,白蒙兀兒,贏得了歐勝獎的歷史。他現在工作在莫臥兒四方,四書講故事的大莫臥兒從 時間到末代皇帝巴布爾,哈杜爾沙阿 Zafar。第一冊將於明年秋季由 Bloomsbury出版。

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2010

0 comments:

Post a Comment